Movement Load metric allows you to quantify the movement of your athletes using the Firstbeat Sports platform.

But what exactly is Movement Load? What should you do with information it provides, and how does it fit alongside the existing data you are already getting? All are valid questions, especially if you don’t have previous experience using external Training Load data.

This blog will answer those questions as well as provide practical examples to help you visualize how to get started with Movement Load.

Want to learn more about the Firstbeat metrics? Download our training load guide for coaches here.

What is Movement Load?

Let’s start at the beginning. What is Movement Load? Understanding this is fundamental to making the most of the data.

Movement Load uses data from the embedded accelerometer in the Firstbeat Sports Sensor which collects every movement from the athlete across all three planes – sagittal (front/back), frontal (left/right), and transverse (top/bottom). A scaling factor is then applied to give a single number for movement that has taken place over the duration of a session.

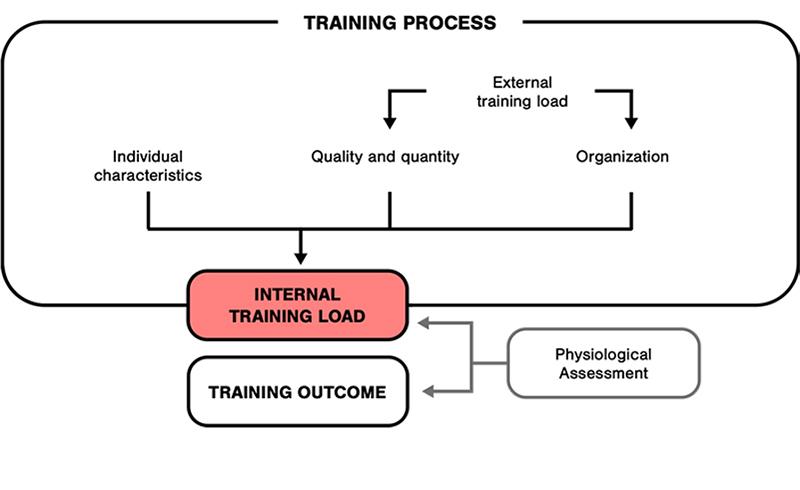

Like TRIMP, Movement Load quantifies the load of a session. The difference being Movement Load captures the external Training Load whereas TRIMP is the internal Training Load.

The Training Process involves several elements, including internal and external training load, to produce the Training Outcome. (Adapted from Impellizeri, et al., 2005).

What do I do with Movement Load data?

So, how can you actually use Movement Load data and how does it fit within the data you already collect?

The training process outcome is determined by the internal load which, in turn, is determined by the external load. The pre-existing Firstbeat Sports metrics cover the internal load element. Movement Load handles the external. Adding Movement Load means all the ‘controllable’ elements are now covered in Firstbeat Sports. This allows us to establish how much external load it takes to elicit a certain internal load – and use this data to make decisions.

In short, Movement Load adds context to your internal load. In practical terms it gives you more insight into why a particular internal load has occurred.

For example, in a soccer match a player may have a higher TRIMP in the second half compared to the first. The first conclusion you might reach is that they have fatigued over the course of the game. However, it may be that they moved more in the second half perhaps as a result of being behind and having to chase the game. With Movement Load, we now get an insight into whether our player was tired and became less efficient, or whether they simply moved more. This can then be used to inform future training and address, e.g., is conditioning late in games an issue or is it a technical/tactical issue that is causing a player to have to complete more work?

What other practical uses are there for Movement Load data?

Comparing Movement Load to TRIMP allows you to test without testing. Do you get more movement for the same TRIMP, or the same movement for less TRIMP? Either of these suggests an improvement in fitness, especially if assessed from a like-for-like activity. Of course, it doesn’t give an explicit result like a YoYo or 30-15 IFT, but how often do you get the opportunity to actually run those tests during a season?

Testing without testing

By looking at the relationship between internal and external load regularly using Movement Load and TRIMP you can constantly get a picture of how your athletes are doing without having to do anything outside of your normal training.

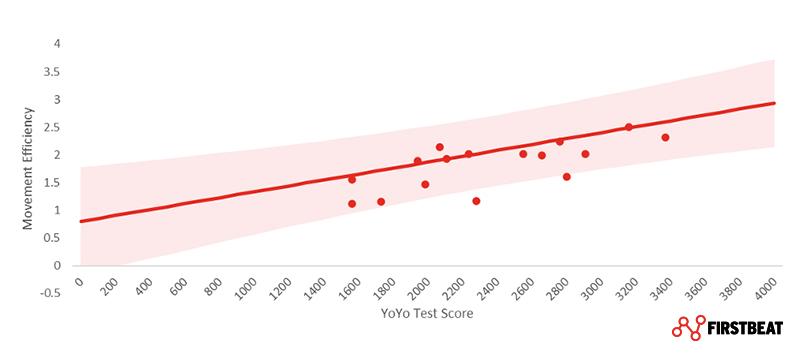

The below graph is a great example of this. It plots players’ YoYo test scores on the X-axis against ratio between Movement Load and TRIMP (what I will refer to as movement efficiency from here on) on the Y-axis.

YoYo test scores plotted against movement efficiency.

It’s a small sample, but we can see some sort of relationship between the YoYo scores and movement efficiency. This backs up the idea that we can use this ‘movement efficiency’ as a regular conditioning test from within sessions themselves.

As mentioned earlier, you should compare like-for-like activity when using movement efficiency for testing. This is important whilst also offering a glimpse into another use for the data.

Selecting appropriate drills

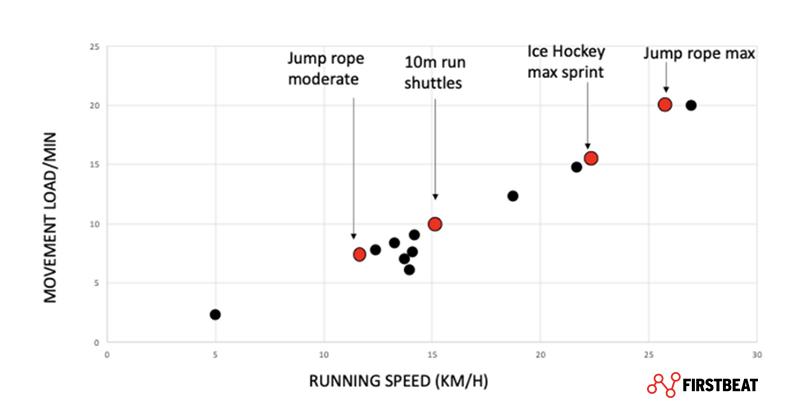

Different activities/drills will likely have different effects on internal load. The quicker you run (up to a point) the more efficient you become from an energy usage perspective (Cavagna, 1977; McArdle, 2000). Sessions with big areas that allow high-speed running will accumulate Movement Load at different rates to tight area work, whereas tight areas with lots of small movements will be very demanding internally relative to the movement.

Understanding this lets you build profiles of the different drills, getting an idea of what they offer in terms of both TRIMP and Movement Load and using the information to select appropriate drills for the desired physical outcomes.

Movement Load/min data allows you to compare drills of different sizes.

Movement Load data allows you to dig deeper and learn more about your athletes than ever before. This blog is not an exhaustive list of how this data can be used but hopefully give you some starting points for what is possible.

Have any questions, or want to start using Movement Load in your setup? Whether you are an existing Firstbeat Sports user or considering joining us and our 1,000+ elite level clients, get in touch with us here!

References

Cavagna, G.A., & Kaneko, M. (1977). Mechanical Work and Efficiency in Level Walking and Running. The Journal of Physiology, 268(2), 467-481.

Impellizeri, F., Rampinini, E., & Marcora, S. (2005). Physiological Assessment of Aerobic Training in Soccer. Journal of Sports Science, 23(6), 583-592.

McArdle, W.D. et al. (2000). Energy Expenditure at Rest and During Physical Activity. In: McArdle, W.D. et al., 2nd ed. Essentials of Exercise Physiology, USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

You might also be interested in

One Year of the Firstbeat Sports Sensor and Live App

It has been one year since we launched the Firstbeat Sports app and Sensor – introducing our most flexible, efficient and in-depth internal load monitoring solution yet with the aim to bring true mobility to coaching.

How to Use Training Effect: The Firstbeat Sports Feature that Measures the Impact of Training

In this article, we look at how Training Effect is calculated, the Training Effect scale, and how it is visualized in Firstbeat Sports.