This article is written by Domenik Theodorou, a Firstbeat Sports client and Performance Coach at RASTA Vechta, a professional basketball team competing in the Basketball Bundesliga (BBL). Prior to his current role, Domenik also worked at Bamberg Baskets and BG Göttingen. In this article, Domenik shares practical advice and tips on using Firstbeat during Return to Competition.

The primary goal of a Return to Competition (RTC) is to expedite the recovery of a player while simultaneously minimizing the likelihood of re-injury.

In this article, I’ll outline my strategy for RTC processes and elaborate on how I use Firstbeat to improve decision-making during this phase. I categorize RTC into “off-court” and “on-court” rehab, with a particular emphasis on the important role of integrating Firstbeat, especially during the on-court segment of RTC.

Off-Court Rehab – Strategies and Insights

Let’s assume a player sustains an ankle injury and, following consultation with our medical team, is likely facing a rehabilitation period ranging from 4 to 5 weeks. We consistently aim to introduce our athletes to training at the earliest possible stage, prioritizing safety, as immediate loading holds the potential to shorten the RTC.

Within one or two days post-injury, the player typically begins weight room exercises with a four-day program designed for use up to six days per week. I focus on loading the injured tissue toward its current capacity while training the rest of the body as normally as possible. The overall goal is to improve the local tissue quality while decreasing pain and increasing function.

In addition to lifting, I include extra aerobic endurance training on a stationary bike, chosen for its low joint impacts. With the onset of conditioning work, I truly start integrating Firstbeat.

Provided there is no discomfort, I introduce the Echo bike for our athletes because it engages the upper body, resulting in higher heart rates compared to a regular stationary bike.

Conditioning sessions differ in volume and intensity throughout the week and usually take place during team practices at the side of the court to allow players to focus on team tactics at the same time.

The Three Phases of On-Court Rehab

After receiving clearance from our doctor, we start the process of on-court RTC, preparing our athlete for the demands of basketball to improve his sport-specific capacity. The on-court training sessions complement the off-court rehab and are structured into three separate phases.

Phase One – Working One-on-One with the Injured Player

During phase 1, I work individually with the injured player in a one-on-one setting. Before starting the first training session, I set a goal for completing phase 1 by examining the player’s average Movement Load (ML) during high-intensity team practices.

By utilizing Firstbeat to monitor each player’s training load, I have access to a database that enables me to review the average practice loads on different practice days (GD-4, GD-3, GD-2, GD-1).

Team practice on GD-3 generally is the most demanding training session of our week. If the injured player averages a ML of 245 on GD-3, that becomes our benchmark for completing Phase 1 of the on-court RTC.

The player must successfully complete two consecutive training sessions, surpassing a ML of 245 without encountering setbacks during training or the following day.

It’s crucial to note that individual workouts, especially in the initial stages of phase 1, must align with the constraints of the injury. Typically, our target for the first session is a ML of around 100. The next session on the following day depends on the athlete’s feedback. If the ankle feels good, we aim to increase the load; if there’s discomfort, we either skip the workout or attempt to reduce the load.

Ideally, we seek ML increments of 25-50 in each training session until the desired goal is achieved. The progressions during Phase 1 will vary for each player and rely on the extent of the injury.

As a general guideline, I suggest that the more time a player spent in off-court rehab, the smaller the increments should be for advancing the on-court rehab.

Phase Two – Structured Progression and Increased Intensity

During phase 2, the player also must complete two back-to-back individual workouts, passing the 245 ML threshold. The notable change in this phase involves the addition of an assistant coach who enhances the technical and tactical demands. This modification makes the training more position-specific and raises its intensity. Having two coaches dedicated to one player simply allows for more density. To advance to Phase 3, again, the player must provide a good report after training and the following day.

At this point, you might ask yourself how we structure the content of each session. While I can’t cover all the details here, I’m a big fan of the control-chaos continuum explained by Taberner et al in 2023. In simple terms, we aim to move from “high control” to “moderate control” to “moderate chaos” in phases 1 and 2, and finally, reach “high chaos” in phase 3 of the on-court RTC.

Before moving to phase 3, our team doctor re-evaluates the player. Once cleared, we slowly bring the athlete back into our team practices. Here’s how we progress:

- Team practice 1: 1 contact drill (half court)

- Team practice 2: 2 contact drills (2x half court)

- Team practice 3: 3 contact drills (2x half court, 1x full court)

- Team practice 4: full training participation

Phase Three – Back to Team Practice

In phase 3, we limit the player to just one basketball practice per day. For instance, if the team has a morning session combining individual basketball workouts and lifting, a player in phase three would only do the morning lifting to stay fresh for the team practice in the evening.

If the player successfully completes phase 3 without any setbacks, we view them as fully back in practice. Ideally, we prefer the player to go through a full week of practice without limitations before clearing him for games. While this is our general plan, it can sometimes be subject to change.

More Firstbeat Parameters to Watch During RTC

Another important parameter that we closely monitor during the RTC is the Acute Training Load (ATL). It is calculated using the TRIMP metric, which adds up all their training from the past 7 days.

Having access to the player’s pre-injury training data provides insight into the typical ATL levels. Our goal during RTC is to gradually increase the ATL up to a level that is close, or ideally even higher, than what the athlete was used to during regular practice and game participation.

Narrowing the gap between the athlete’s ATL when healthy and their current level during RTC minimizes the gap between rehab and returning to regular practice conditions. In the end, I want to point out that making this happen is easier said than done, as it is quite challenging to simulate the demands of regular practices and games during rehabilitation.

Aside from monitoring ATL, we also pay attention to the Chronic Training Load (CTL) which shows the rolling average of ATL over the last 28 days. Depending on the severity of the injury, we aim to maintain CTL as best as possible, as higher CTL is associated with a lower risk of injury as long as we get to these loads safely.

This is why we want to start off-court RTC as soon as possible after an injury – to lessen the extent of dropping CTL. Keep in mind that choosing to maintain CTL always depends on the extent of the injury, the context of the player, and the resources available to us.

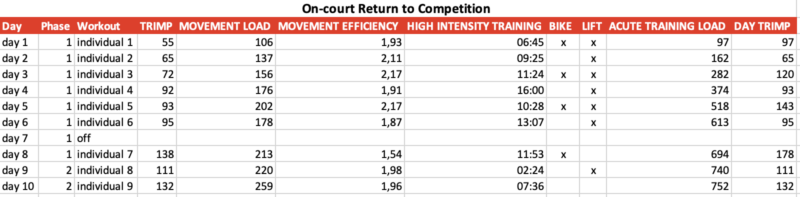

Figure 1 illustrates phases 1 & 2 of an athlete during on-court RTC after an ankle injury. Our goal for phase 1 was to reach a target ML of 220. This is a very good example because it shows that plans don’t always unfold as expected and that rehabilitation will never be a linear process. Individuals 6 & 7 were meant to be higher, but time constraints forced us to adjust.

However, positive feedback from the player after each workout led us to conclude that he was ready for phase 3 – the gradual re-introduction to team practice. Before the injury, the ATL from this athlete usually ranged from 750 to 950, and we managed to bring him close to these values. Figure 1 also shows that the ATL started at zero because the athlete got sick for 8 days right before starting phase 1 of the on-court RTC.

To better understand how the movements in the advanced phases of the RTC relate to previous team practices, I also like to examine Movement Intensity (MI), which represents the average ML per minute. Although my main focus lies in closely monitoring MI during the later stages of the on-court RTC, I also ensure to pay attention to it during phase 1, gradually ramping up MI levels.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 2 shows a workout during phase 2 of our on-court rehab while Figure 3 displays a high load team practice of the same player. Despite our efforts to mirror the movement intensity demands of team practices during rehab, we slightly find ourselves falling short. We manage to simulate the density aspect, yet we struggle to reach peak output levels.

This is why we prefer a stepwise re-integration into team practices providing players with the opportunity to slowly readapt to practice loads. While we may not fully meet the mechanical intensity requirements during RTC, we can still expose athletes to training loads that will prepare them in the best possible manner.

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize that what I have outlined is simply my framework for navigating RTC processes. I’m happy to have a plan that I can share not only with the coaching staff but more importantly with the player. This promotes transparency and has the chance to boost the athlete’s commitment to rehabilitation. Introducing a plan also provides plenty of opportunities for education in the areas of injury, training, nutrition, and recovery.

In professional sports, time is always of the essence, and there are situations where making quick decisions and taking calculated risks are necessary. Nonetheless, it will always be our goal to build up the training load systematically during RTC.

This is precisely where Firstbeat enhances our decision-making in rehabilitation by breaking down the on-court rehab into distinct stages until we reach pre-injury benchmarks. Quantifying the training load not only prevents overtraining but also allows for ongoing progress monitoring, fostering a sense of accomplishment throughout the rehabilitation journey.

If you’re interested in learning more about how I incorporate Firstbeat as a daily screening tool throughout the season to identify fitness trends in our players, you can explore the details in my initial blog post here.

I am always happy to connect and chat about S&C work. Please send me a message on Instagram @domceps if you would like to connect.

Learn more from Domenik by watching our free webinar recording – Mastering Data-Driven Decisions in Pro Basketball.

References

- Taberner, M. et al 2023 Progressing On-Court Rehabilitation After Injury: The Control-Chaos Continuum Adapted to Basketball. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2023; 53: 498-509

You might also be interested in

How I Use Firstbeat in Professional Sports to Identify Trends in Players’ Fitness

This article is written by Domenik Theodorou, a Firstbeat Sports client and Performance Coach at RASTA Vechta, a professional basketball team competing in the Basketball Bundesliga (BBL). Before his current…

From Data to Court – Using Firstbeat in Women’s Basketball to Optimize Training and Recovery

In the world of competitive sports, every advantage counts. For women athletes, whose training needs and recovery patterns often differ from their male counterparts, understanding the intricacies of internal load…

Shooting For The Top Again with RASTA Vechta and Firstbeat Sports

RASTA Vechta is a basketball team currently playing in the Pro A, the second division of professional basketball in Germany. We recently spoke with Vechta’s Performance Coach, Domenik Theodorou, to…