My previous blog in this series discussed heart rate variability and how it can be used to monitor stress and recovery. This time, the focus is on what stress and recovery mean in the context of wellness and lifestyle, and how understanding that is helpful for comprehensive lifestyle management.

Most simply defined, stress is a physical response that helps us survive. When we face physical or mental stress, the body switches to a fight or flight mode and the sympathetic branch of the nervous system takes over to prepare us for action: various hormones and chemicals are released, heart rate and blood pressure increase, heart rate variability decreases, and blood flow is directed to where it is most needed (for example muscles). A physiological stress reaction can be caused by internal (e.g. overload, fatigue, pain, or fever), external (e.g. alcohol, physical workload or heat) or psychological / social stressors (e.g. anxiety, fear, pressure, work stress).

Stress Belongs to Life but Needs to be Managed Right

Psychologically, stress is defined as a situation where the demands that a person is faced with are greater than the available resources. Stress can also be characterized as the body’s physical and mental adaptation to real or perceived change and life’s challenges (stress resilience or coping). An appropriate level of stress (a.k.a. drive or activation level) at work is associated with better productivity and performance, but when the stress level is too high for too long, performance starts to suffer.

Your Perception of Stress Matters

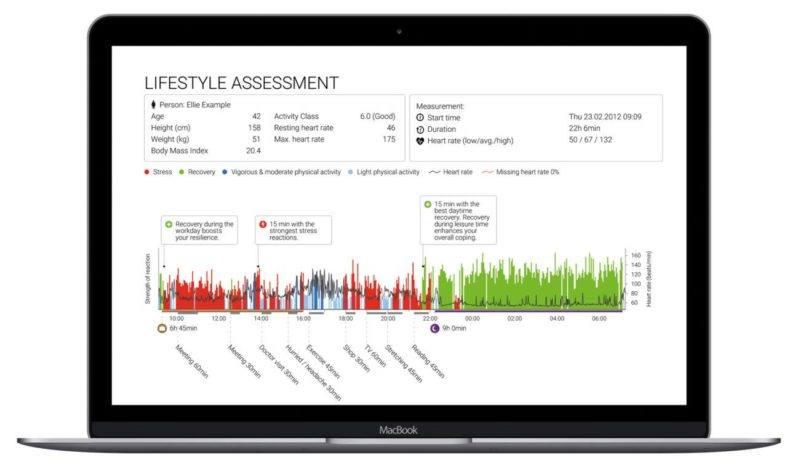

Depending on your perception and the context, stress can be positive, such as an exciting new challenge, or negative, such as excessive work pressure or too many demands. While the acute physiological reaction to either kind of stress is similar, the ‘aftermath’ differs – we can usually turn off and recover from positive stress, whereas negative stress lingers on and keeps the body in a state of stress even when we rest, or when the acute stressor is no longer present. This is illustrated in Figure 1 with two examples from a Firstbeat Lifestyle Assessment report. However, if you tend to thrive on the constant adrenalin rush of positive stress and feel that you hardly need to sleep because you are so positively charged, keep in mind that even positive stress can eventually run you down and result in exhaustion if not managed right and balanced with recovery.

Figure 1. These Firstbeat Lifestyle Assessment graphs illustrate that it’s not stress (red) that determines well-being, but our ability to recover from it (green). We can turn off positive stress e.g. during sleep or a peaceful moment, whereas negative stress can keep the body wired even during sleep.

The negative health consequences of chronic stress are backed by a lot of research. For example, anxiety, depression, digestive problems, heart disease, Diabetes 2, sleep problems and memory and concentration impairments are associated with long-term activation of the stress-response system. This emphasizes the importance of healthy stress management – and brings us to recovery.

Recovery Recharges the Body

We face challenges daily that initiate a stress reaction, but when the challenge is over, our physical and psychological state should return to the pre-stress situation (homeostasis). This physiological process is called recovery. It means that the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system becomes dominant (illustrated by the green color in Fig. 1), lowering the body’s activation level (decreased heart rate, increased heart rate variability) and functioning as the body’s brake.

Our psychophysiological resources are restored during recovery – and sufficient recovery is necessary to overcome the effects of stress. Sleep is naturally the most crucial time for recovery, but periodically, we should also be able to gain some recovery moments during the day, for example at work or in the hours before bed.

Read our top 10 tips for a better sleep →

Identifying factors that help or hinder recovery is not easy because our perception of stress and recovery does not always match reality. Just because we are asleep does not mean that we get optimal recovery during sleep. Recovery does not happen by turning on a recovery switch or closing our eyes more tightly, and strong will or tough attitude do not help if we constantly overload our body, ride the stress-rollercoaster, or make poor lifestyle choices. Good recovery requires smart choices and an attitude change, especially for people who are used to overdoing it and pushing themselves beyond their limits.

Certain factors are known to compromise good recovery. For example, alcohol, illnesses, stress, excessive load (work + other stressors = load of life) and worries can weaken or even completely block the recovery process by keeping the stress system switched on. On the other hand, sufficient good-quality sleep, good physical fitness, mental well-being, balanced nutrition and a positive attitude support normal functioning of the recovery process and the re-building of our physical and mental resources.

Here are a few practical tips for ensuring good recovery; more examples and tips can be found in some of our previous blogs.

- Get enough good-quality sleep, especially during demanding periods of life.

- The few hours before bed matter! Learn to finish your daily chores earlier & slow down before bed.

- Appropriate physical activity (tailored to your fitness level and life situation) and healthy nutrition promote good recovery during sleep.

- Minimize alcohol use and avoid strenuous exercise close to bedtime.

- Learn to downshift during busy days, for example with mindfulness or relaxation.

Firstbeat Lifestyle Assessment provides valuable insights for better management of your personal stress and recovery balance. The Body Resources graph illustrates this balance over a 3-day measurement, highlighting that stress itself is not a problem as long as it’s balanced with sufficient recovery.

Figure 2. The Body Resources graph provides a visual representation of whether we are depleting (top) or recharging (bottom) our battery, by looking at the balance between stress and recovery over 24h periods.

Interested in learning more about your own stress and recovery levels?

You might also be interested in

Top 5 Tips for Charging Your Batteries and Recovering During the Summer

There is more to a vacation than closing the office door and plugging in the personal re-charger. Here’s our TOP 5 list of things to remember on a vacation.

The Big Picture of Wellness – Stress Management, Good Sleep and Nutrition Go Hand in Hand

Weight management and healthy eating are issues that wellness professionals face every day with their clients.